The report on behalf of the Federal Ministry of the Interior, Building and Community (BMI) and the Federal Institute for Research on Building, Urban Affairs and Spatial Development (BBSR) within the Federal Office for Building and Regional Planning (BBR) is managed, carried out and written in cooperation between the BBSR and the German Institute of Urban Affairs (Difu) as well as nine actively participating cities/municipalities of different size and geographical location, namely Baruth/Mark (4,200 inhab.), Bremen (570,000 inhab.), Cologne (1,100,000 inhab.), Darmstadt (160,000 inhab.), Eltville at the Rhine (17,000 inhab.), Juist (1,500 inhab.), Mannheim (310,000 inhab.), Niebüll (10,100 inhab.) and Stuttgart (635,000 inhab.). Due to a methodological focus and selection of content within SDG 11, many other important measures of municipal sustainability cannot be addressed in equal detail here; they may be the subject of further in-depth analyses.

The Corona pandemic has significantly intensified the conflict of goals, as municipalities must weigh the extent investment activities and budget consolidation can or should be postponed in the face of rising social expenditures for increasing numbers of unemployed and short-term employees. At the outbreak of the global Corona pandemic and subsequent contact restrictions imposed as a result - even though the complete picture for the public budgets is only slowly becoming apparent. In addition, some of the municipalities in Germany were already deeply in debt prior to the Corona pandemic and despite the significant fiscal and budgetary recovery of recent years. With the economic lockdown during the global Corona pandemic, the forecasts for public budgets in the Federal Republic have changed dramatically. In view of collapsing tax revenues and budget deficits, continuation of the consolidation path of previous years will no longer be possible. With falling revenues and rising expenditures, it can be assumed that municipal debt will increase significantly again for the time being.

At the beginning of 2020, it was still assumed that the target of reducing greenhouse gas emissions for this year would be missed, nevertheless, the Corona pandemic and a mild winter have meant that Germany was able to achieve its climate protection target for 2020 after all.

The state of public transport in Germany under the current Corona pandemic conditions is quite ambivalent, with passenger numbers recorded as declining for the first time in decades. Prior to the pandemic, passenger growth and a long-standing reluctance to invest due to the unclear financial situation resulted in a public transport service that has reached or already exceeded its peak hour capacity limits in cities and on urban-rural connections.

Awareness of sustainability issues among politicians and the general public in Germany has grown significantly in recent years and is now expressed in various guiding principles and strategies that are continuously developed. With the adoption of the New Leipzig Charter urban development policy realigns in the sense of transformative urban redevelopment and thus in the sense of the New Urban Agenda. Municipalities are increasingly obliged to embed their planned urban development measures conceptually in corresponding sustainability strategies. After all, the settlement structure, topography and demographics as well as the social, economic and fiscal framework conditions of the more than 11,000 municipalities in Germany reveal considerable heterogeneity. Due to the federal structure of Germany, urban development policy is shaped partly by shared and partly by autonomous responsibilities of the individual federal levels. This increases the need for political and administrative coordination in a cross-cutting policy area such as urban development policy with its various interfaces to other policy areas. It is not uncommon for the topic of sustainability to be advanced in municipal administrations by individual forerunners. In view of the technical and practical challenges involved in implementing the New Urban Agenda, municipalities mention a lack of resources as an obstacle to the accelerated expansion of their sustainability activities.

The New Urban Agenda refers directly to the agreements of the Paris Climate Change Agreement (Paragraphs 6, 79) and explicitly addresses the issues of climate change mitigation and adaptation in more than a dozen paragraphs. The importance of climate protection and adaptation measures is often addressed in connection with the resilience of infrastructures, transport and energy services as well as the economy by calling for a strengthening of resilience in the event of (climate-related) disasters.

The topic also has great significance in municipal practice, where climate protection is often equated with sustainable urban development. Of the many measures for municipal climate protection that have received special media attention in the past two years, the "climate emergency" declared by various German municipalities underscores the degree of influence public pressure has on the climate policies of cities and municipalities. In 2019, not least as a response to the Fridays for Future protests, Konstanz was the first city to make a resolution recognising the insufficiency of previous climate protection measures and the need for additional measures. Since then, more than 70 municipalities in Germany have adopted the so-called "climate emergency" or launched actions to mitigate climate change. The momentum of resolutions has slowed in the wake of the Corona pandemic, but the number of active municipalities continues to grow. Research on climate emergencies declared so far suggests that many resolutions tend to be somewhat general and lack the backing of concrete actions and resources. At the same time, however, solid building blocks, such as the initiation of climate protection concepts or the systematic review of all municipal measures for their climate impact, do exist, which go far beyond a mere symbolic policy.

Examples of municipality commitment are evident in the annual "Climate Active Municipality" competition organised by the Federal Ministry for the Environment, Nature Conservation and Nuclear Safety (BMU) and the German Institute of Urban Affairs. Since 2009, more than 100 municipalities and regions across Germany have received awards for exemplary projects on climate protection and climate impact management. Awards are made in the categories "Resource and Energy Efficiency", "Climate Adaptation" and "Climate Activities for Participation". The award-winning projects of the municipalities are characterised by a very high diversity and are considered best practice examples for other municipalities that would like to address the topic from the perspective of their individual structures.

Successful climate protection and climate adaptation management by counties, cities and municipalities requires institutional framework conditions that are created at the higher levels of the federal and state governments and also within the municipalities themselves. The New Urban Agenda takes this into account, especially with Paragraph 79, which states: "We commit ourselves to promoting international, national, subnational and local climate action, including climate change adaptation and mitigation, and to supporting the efforts of cities and human settlements, their inhabitants and all local stakeholders as important implementers […]".

Despite financial and personnel constraints, which many municipalities regularly report in different contexts, the topic of "climate change" is high on the political agenda of many municipalities. Almost all partner municipalities have prepared and adopted climate protection concepts. A survey of municipalities by Difu draws a similar conclusion, in which increasing numbers of municipalities state that they have prepared or are currently preparing a climate protection concept.

Paragraph 79 of the New Urban Agenda addresses the sector-specific reduction of various GHG emissions in order to “be consistent with the goals of the Paris Agreement adopted under the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, including holding the increase in the global average temperature to well below 2 degrees Celsius above preindustrial levels and pursuing efforts to limit the temperature increase to 1.5 degrees Celsius above preindustrial levels".

The basis for municipal climate management is usually the balancing of local GHG emissions. According to the Difu Municipal Survey 2020, the majority of German municipalities have already drawn up at least one CO2 balance sheet. Regular analysis of municipal emissions, i.e. monitoring, on the other hand, is rarely performed, and is predominantly left to larger cities, if at all.

The development of sectoral GHG emissions in a municipality, as exemplified by Stuttgart in Figure 12, also reflects the development at the national level. The greatest savings can be observed in industry and commerce, which can be explained by the tertiarisation of the economic structure and increased energy efficiency, among other things. Similarly, emission reductions can also be observed in the private household sector, interacting with an increased number of inhabitants. These have their origin, among other things, in the energy refurbishment of existing buildings and the completion of residential buildings with renewable energy heating (cf. Figure 16). In addition, the increased share of renewable energies plays a major role in almost all sectors: the electricity GHG factor has improved by around 30% in the period shown. In conjunction with the positive development of GHG emissions at municipal facilities, the commitment of the counties, cities and municipalities to climate protection becomes visible here. All participating partner municipalities report that they provide offers to sensitise and inform citizens on the topic of climate protection and renewable energies and use renewable energies on municipal properties. In contrast, few changes have occurred over time in the transport sector. Distribution across different means of transport, remaining for example relatively constant in passenger transit for years (cf. 3.2.1 Modal split). Freight transport is actually gradually shifting away from more environmentally friendly modes of transport to road transport. In addition, technical efficiency gains in both areas are being eroded by larger and more powerful vehicles and longer driving distances.

The share of transport-related GHG emissions can vary considerably between municipalities (see Figure 13). In addition to the control options of a municipality, city-specific characteristics such as settlement, population and economic structure play a major role with regard to sectoral GHG emissions. In Mannheim, the formative metal processing and chemical industries are recognisable in the GHG balance, while Stuttgart's strong service sector and the corresponding building stock dominate its own analysis.

With Paragraph 54, the New Urban Agenda calls for the "generation and use of renewable and affordable energy" and subsequently refers to "reductions in renewable energy costs give cities and human settlements an effective tool to lower energy supply costs ". Promoting energy efficiency and sustainable renewable energy and ensuring "universal access to affordable, reliable and modern energy services" are also explicitly called for in Paragraph 121.

In addition to biomass, photovoltaics and hydropower, the renewable energy landscape in Germany is primarily characterised by wind power. This results in a north-south divide in the share of renewable energies in gross electricity consumption in a nationwide comparison (cf. Figure 14). While the coastal north of Germany, which is favoured by wind, produces far more renewable electricity than it consumes, the effect is reversed in the south of the country, where it is intensified due to prevailing industrial structures.

At the municipal level, only isolated statistics exist on the expansion of renewable energies. More than half of the municipalities surveyed in 2020 responded that they have conducted or are planning to conduct a systematic study on the use of renewable energies, including an expansion of photovoltaics and wind power in their own municipal properties. Corresponding survey results inform residents of expansion possibilities. But the majority of municipalities do not pursue concrete expansion targets.

The provision of space heating in residential buildings is an important starting point for municipal climate protection, accounting for about two thirds of final energy-related building energy consumption in Germany. The New Urban Agenda commits at all levels “to develop sustainable, renewable and affordable energy and energy-efficient buildings and construction modes" (Paragraph 75). Solar, the use of heat pumps, district heating and biomass can contribute significantly to a reduction in fossil energy consumption and thus CO2 emissions. Since the nationwide rates of new construction are less than 1%, the importance of new buildings results indirectly from their exemplary function for measures that can later be transferred as innovations to the existing building stock and are associated with lower investment costs due to broader market incorporation.

The activities of 2016 to 2018 show an increase in the share of completed residential buildings with renewable heating energy in all partner municipalities. Here, most municipalities measure within in a range of between 30 and 60% and a slight increase in the rate, reflecting the Germany-wide trend. In contrast, rates in the county Aurich, in which the island municipality of Juist is located, and Bremen, where the rate remains in single digits, are exceptions.

Paragraphs 80 and 101 directly address adaptation to climate change: "We commit ourselves to supporting the medium- to long-term adaptation planning process, as well as city-level assessments of climate vulnerability and impact, to inform adaptation plans, policies, programmes and actions that build the resilience of urban inhabitants, including through the use of ecosystem-based adaptation." (Paragraph 80).

Measures to adapt to climate change are planned and implemented in the municipalities depending on how they are each individually affected - whether through geographical conditions, such as proximity to the coast, or urban planning conditions that favour heat islands, for example. Unlike in municipal climate protection, where responsibilities are organised more centrally, climate adaptation measures are more difficult to record or even quantify. They are often implemented in the planning or in concrete urban development measures of various departments, but are rarely absorbed under the heading of climate adaptation. All participating partner municipalities report that adaptation to the consequences of climate change is taken into account in urban planning and development, and that an interdisciplinary or interdepartmental working group on climate adaptation is active in their own city.

In the actual implementation of climate adaptation measures, the municipalities primarily note the ecological reconstruction of urban green spaces, energy-efficient building refurbishment, flood protection and citizen information activity. Adaptations of the transport infrastructure, on the other hand, are not among the most frequently noted measures. Good examples of climate change adaptation measures are recognized in the biennial "Blauer KomPass" competition organized by BMU and UBA and presented in the German Environment Agency's so called Tatenbank (database of actions).

Urban development strategies summarised under the term smart city, and characterised by the use of new types of ICT solutions, are a new approach to pushing climate protection and climate adaptation measures at the municipal level. Even though corresponding approaches are still in their infancy in Germany, many cities hope to improve their future viability through so-called "smart solutions", to become more digital and to network individual areas such as energy, buildings or mobility more closely and sustainably with one another. Digital communication systems, information technology collection and processing of exponentially growing amounts of data all bring about diverse, and disruptive changes (digital transformation). They and are currently also fundamentally changing cities and their public services (Libbe 2018 and 2019). Paragraph 66 of the New Urban Agenda also commits "[…] to adopting a smart-city approach that makes use of opportunities from digitalization [...]".

Against this background, the federal government's implementation strategy "Shaping Digitisation" focuses primarily on temporary model projects that serve to develop and test new technologies or the digitisation of administrative processes. In contrast, digitisation issues have so far played a relatively subordinate role in the policy fields, with regional and municipal relevance that are geared towards spatial and land use design. The topics of "Smart City" and "Smart Country" are however, now also addressed by the "Smart City Charter - Sustainably Shaping Digital Transformation in Municipalities" (BBSR, BMUB 2017) and their corresponding funding programmes. The Future Radar Digital Municipality of the German Association of Towns and Municipalities (DStGB) has repeatedly shown that municipalities recognise the importance of digital transformation (Hornbostel et al. 2018, 2019), but integrative approaches that also take into account urban planning and environmental policy remain rudimentary at best. Nevertheless, digitalisation is a field of action that is not only particularly suitable for cross-policy coordination, but also virtually forces it. The fact that in some cases entirely new content and technologies have to be developed from all policy areas and flanked by social and data protection impact assessments, should be reason enough in the future to combine administrative capacities and push for interdepartmental approaches. However, the existence of nationwide broadband and mobile networks with fast transmission speeds is considered the backbone for digital applications and can be noted as a model for the linking of the 2030 Agenda and the New Urban Agenda.

Digitisation as a global process and as a strategy for coping with the consequences of climate change offers opportunities for more efficient administrative action and more environmentally and climate-friendly services of general interest. However, it also poses risks with regard to increasing disparities in spatial development, and increasing energy and resource consumption. Although cities' digitisation strategies are increasingly being placed in the context of overarching urban development goals, the question of the sustainability of digitisation itself has not yet been answered satisfactorily (WBGU 2019). Systematic monitoring and comprehensive evaluation of digitisation strategies, including corresponding projects - especially with a view to their sustainability - has not yet been undertaken in the Federal Republic as a whole or at the municipal level. The goals of the 2030 Agenda also remain vague with regard to digitisation in the local context. There is no dedicated reference to the SDGs, but rather only an indirect mention in the sub-goals of SDG 4 "Quality education", SDG 9 "Industry, innovation and infrastructure" and SDG 16 "Peace, justice and strong institutions".

The concept of the "smart city" of the New Urban Agenda refers to the provision of environmentally friendly alternatives and opportunities to promote sustainable economic growth (Paragraph 66). In doing so, the opportunities of digitalisation, clean energies and innovative technologies are to be used and made accessible to the public, especially for women and girls, children and youth, people with disabilities, older people and people in precarious living situations (Paragraph 156). The goals of a so-called "Climate Smart City" are specifically formulated in several Paragraphs (e.g. 34, 50, 66, 74, 156, 160). For example, Paragraph 34 of the New Urban Agenda provides for equitable and affordable access to sustainable basic physical and social infrastructure for all, without discrimination. Moreover, technological innovations can have a positive impact not only on digitalisation, but also on mobility and the climate: In the case of transport and public transport systems, this should “reduce congestion and pollution while improving efficiency, connectivity, accessibility, health and quality of life” (Paragraph 118).

In a nine-partner municipality cooperation, various sustainability activities were noted that indicate the current implementation status of the smart city concept in the relevant cities and municipalities. For example, two thirds of the municipalities have developed a long-term strategy for dealing with big data. However, the achievement of goals and the impact of the corresponding digital agendas or digital strategies have not yet been verified in any of the participating municipalities through long-term monitoring. This makes tracking the effectiveness of the corresponding strategies difficult. More than half of the municipalities state that digital platforms are already in use today, making information that is relevant for democratic decision-making processes more available locally. In this regard, these municipalities have an inclusive and activating approach that enables the participation of all citizens. Furthermore, these municipalities state that they and/or their municipal companies have sovereignty over their data that is relevant for the fulfilment of their tasks. Nevertheless, the digitalisation efforts of most municipalities in Germany remain in the early stages. The use of digital solutions to combat climate change in the sense of a Climate Smart City is therefore still a topic for the future.

According to the 2020 Difu Municipal Survey, about half of the municipalities state that they have or will have climate adaptation-relevant information and data. At the same time, the vast majority of cities report that interdepartmental cooperation on climate adaptation has not yet been established within local government. In order to be able to use the potential of digitalisation for the socio-ecological transformation at the local level, the very structures that can be considered a prerequisite for Climate Smart Cities must be further developed. Three partner municipalities have already indicated that they use digital technologies (e.g. smart grids, smart metering, smart lighting) to support the local energy transition.

The Basic Law, which forms the Federal Republic of Germany’s constitutional framework, contains a provision on state objectives (Article 20a of the Basic Law). It stipulates that “mindful also of its responsibility towards future generations, the state shall protect the natural foundations of life and animals by legislation and, in accordance with law and justice, by executive and judicial action, all within the framework of the constitutional order". The reference to the "constitutional order" in this constitutional article already indicates that sustainability policy in the Federal Republic is organised on a National level. For according to Article 20 (1) of the Basic Law, Germany is "a democratic and social federal state". The municipalities, as a constitutional part of the federal states (the Länder), form their own administrative level and have autonomy of self-administration according to Article 28 (2) GG.

The political and administrative handling of the global trends of our time, such as increasing inequalities, climate change, loss of biodiversity and increasing amounts of waste, has its own underlying rationality and logic in such a multi-level system. This is because responsibility for the development, implementation and financing of political measures that can counter the effects of these noticeably exacerbated global trends, in the sense of the sustainability principle, lies in a shared responsibility with the federal state structure, together with a high degree of local authority ownership. This requires interdisciplinary and multi-level coordination. Negotiation and cooperation processes of this kind are not only time-consuming, but they often lead to a necessary balancing of interests and goods between the different levels and actors, with compromises perceived critically by the media as "agreements based on the lowest common denominator". Nevertheless, a planning counter-current principle comes into play in these negotiations. In fact, this forces the federal, state and local governments to reassure each other when making decisions on sustainability issues, which often have to be made in a very unpredictable environment. Uncertainties arise, for example, from the unforeseeable occurrence of scientifically modelled scenarios on megatrends, including possible consequences for humans and nature as well as the state's ability to act.

In federal multi-level systems, cities of different sizes and geographical locations play a central role in dealing with global megatrends.

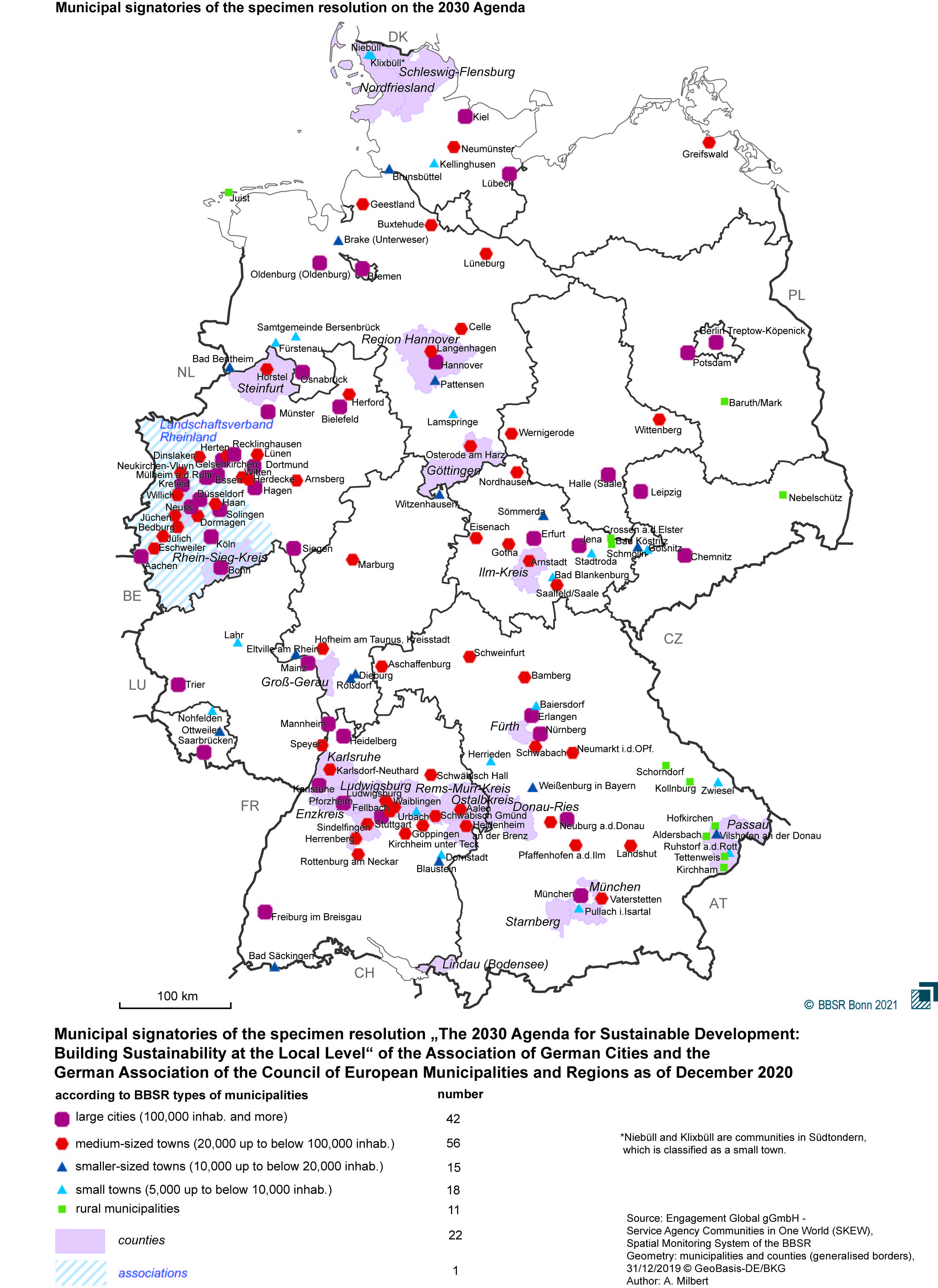

The German Sustainable Development Strategy, as the implementation of the 2030 Agenda in Germany, explicitly takes up this vertical integration. It is the result of many political initiatives that converge in the Committee of State Secretaries for Sustainable Development. Already with the first meeting in 2012 on the topic of "Sustainable Policy for the City of the Future", the resolution adopted in 2015 to establish the "Interministerial Working Group on Sustainable Urban Development in a National and International Perspective" and further joint resolutions with the federal states and municipalities, cross-level coordination on sustainable urban development has been continuously pursued and will again discuss and reaffirm the role of municipalities for sustainable development in June 2021. At the local level, more than 160 German municipalities (as of December 2020) have so far explicitly committed to the 2030 Agenda in a specimen resolution of the German Association of Cities and Towns and the Council of European Municipalities and Regions, thus affirming their role in implementing the 2030 Agenda.

A sustainability policy that implements programmes such as the New Urban Agenda or the 2030 Agenda within a multi-level federal system such as the Federal Republic of Germany requires that municipalities have adequate financial resources. The transformation of infrastructure in urban space including the attendant reorientation of planning, administrative procedures and public sector services, are resource-intensive - even when such processes are realised over extensive time periods. Against this background, arise the questions around the municipalities’ financial and budgetary situation. The Municipal autonomy guaranteed according to Article 28 (2) of the Basic Law “shall extend to the bases of financial autonomy; these bases shall include the right of municipalities to a source of tax revenues based upon economic ability and the right to establish the rates at which these sources shall be taxed". In this respect, the Länder in particular - to which the municipalities are constitutionally assigned, since they do not form a separate level of government - must ensure that counties, cities and municipalities are adequately funded. The financial strength of a municipality in Germany is measured by the sum of the original and the composite tax revenues (such as income and turnover tax on the one hand and property, trade and petty taxes on the other), the contribution and fee revenues as well as the allocations within the framework of the municipal financial equalisation systems of its cities and municipalities.

In constitutional practice, however, the financial and budgetary situation of the municipalities in Germany (do we need to keep saying the federal republic – we know this is all about the levels of the BRD) has been ambivalent for several years. In 2019, for example, the cumulative financing balance of the municipalities of all Flächenländer (area states) in the core and extra budgets - and thus even before the outbreak of the global Corona pandemic - showed a financial surplus for the fifth time in a row. At €5.6 billion (core and extra budgets) and €4.5 billion (core budget), this was lower than in the previous year, but still well above the average of the past decades. The basis for the financing surplus at the municipal level was a continuous overall positive economic situation in 2019. High trade tax and income tax revenues were offset by relatively low social expenditure due to continued high employment, a situation that suffered at the outbreak of the global Corona pandemic and subsequent contact restrictions imposed as a result - even though the complete picture for the public budgets is only slowly becoming apparent.

In addition, some of the municipalities in Germany were already deeply in debt prior to the Corona pandemic and despite the significant fiscal and budgetary recovery of recent years. Of the total of €115 billion with which municipalities and municipal associations were indebted to the non-public sector in the core budget as of 31.12.2019, 72% was accounted for by loans and securities debt and 28% by cash advances, which corresponded to around €32.5 billion. In this context, municipal debt in the non-public sector core budget fell minimally in 2019 from €1,512 per capita at the beginning of the year to €1,499 per capita at the end of 2019. The highly uneven distribution of municipal debt - i.e. credit market debt plus loans to secure liquidity (cash advances) - is an indicator of fiscal disparities in an inter-municipal comparison. Even the distribution of credit market debt per capita in the core budgets shows a considerable disparity in the state comparison. At the top - as in previous years - were the counties and municipalities in Saarland (3,419 euros per capita), Rhineland-Palatinate (2,958 euros per capita) and North Rhine-Westphalia (2,597 euros per capita), where the average per capita debt of the municipalities continues to be well above the average for Germany as a whole. In contrast, the lowest per capita debt was recorded by municipalities in the states of Brandenburg (566 euros per capita), Saxony (548 euros per capita) and Baden-Württemberg (494 euros per capita).

With the economic lockdown during the global Corona pandemic, the forecasts for public budgets in the Federal Republic have changed dramatically. In view of collapsing tax revenues and budget deficits, continuation of the consolidation path of previous years will no longer be possible. With falling revenues and rising expenditures, it can be assumed that municipal debt will increase significantly again for the time being. An April 2020 survey by the German Institute of Urban Affairs (Difu), found that most municipal treasuries anticipated sharply falling revenues for the current year - especially in the area of tax revenues and revenues from economic activity. At the same time, material and social expenditures will likely increase, with about two thirds each assuming strongly increasing expenditures.

The enormous budgetary burdens resulting from the Corona pandemic have additional negative consequences. Since the municipalities make about 60% of all public investments in the Federal Republic with the expansion and reconstruction of various public services and infrastructure (roads, bridges, schools, administrative buildings as well as water and energy supply, etc.), the massive losses of tax revenue are correspondingly significant - even if the medium- and long-term consequences of the Corona pandemic are not yet fully understood. A reduction in investments would mean an end to the painstakingly achieved successes to date. This is because the continuous increase in municipal investments, already visible in recent years, were slated to continue in 2020. According to a survey by Difu, the cities, municipalities (with at least 2,000 inhabitants) and counties had planned investments of around 35.9 billion euros for the 2019 financial year.

With their infrastructure investments, municipalities make an important contribution to transforming cities on the road to achieving the sustainability goals of the New Urban Agenda and the 2030 Agenda. Nevertheless, even before the outbreak of the Corona pandemic, considerable investment arrears existed at the municipal level that were often clearly perceptible to citizens in the form of dilapidated schools, cultural and sports facilities, administrative buildings, and poorly maintained roads, bridges and transport systems. In 2019, the perceived investment backlog of all municipalities with a population of 2,000 or more - according to a projection by the German Institute of Urban Affairs - totalled around 147 billion euros. This is 6% higher than in the previous year. The long-term trend of the past six years shows that the perceived investment backlog rose on average just as strongly as the construction price indices. Hence, although the municipalities invested more in gross terms, price increases meant expenditure was no longer matched in the form of replacement or improvement of infrastructure as would have been the case a few years ago. Moreover, as urbanisation increases, so too does the quantitative and qualitative demand on municipal infrastructure, so that the investment backlog has risen steadily in recent years.

Against this background, the fiscal and budgetary challenges of the municipalities are caught in a "magic triangle" between consolidation efforts on the one hand and rising consumption expenditure requirements and a reduction of growing investment arrears on the other. Again, the Corona pandemic has significantly intensified this conflict of goals, as municipalities must weigh the extent investment activities and budget consolidation can or should be postponed in the face of rising social expenditures for increasing numbers of unemployed and short-term employees. This is because expenditure for compulsory social tasks as well as high consolidation pressure leads (by necessity) to a renunciation of investments, as this is one of the few freely disposable areas of expenditure in municipal budgets. Many municipalities are also obliged to first reduce their deficits, typically accumulated over years, before new liabilities can be entertained. In such a situation, the only recourse remains to cash or liquidity protection loans, which, according to the municipal budget ordinances of the Länder, may actually only be used to finance current administrative expenditure and not investments.

Urban development funding is one of the central instruments for sustainable urban development in Germany. Since the beginning of the 1970s, the federal and state governments have provided financial assistance under Article 104b of the Basic Law for investments in the renewal and development of cities and municipalities. This is intended to strengthen the municipalities as economic and living locations. In addition to Article 104b of the Basic Law, the legal framework for the implementation of urban development promotion is provided by Chapter 2 (Paragraphs 136 to 191) of the Federal Building Code (BauGB) and the currently valid Administrative Agreement on Urban Development Promotion 2020 (VV Städtebauförderung 2020 in conjunction with the Basic Agreement of 19 August 1986). The federal government is thus involved in urban development policy in a field in which it actually has no original competences. The various federal government funding programmes established for the benefit of the Länder and municipalities are characterised by a natural tension. On the one hand, according with international obligations the programmes are intended to provide financial incentives for the realisation of innovative redevelopment, utilisation and integration concepts in (disadvantaged) neighbourhoods and cities, which are hoped to have positive spill-over effects and social, economic and labour market policy consequences for the entire city. On the other hand, mixed financing forms of this kind always represent a "disruptive impulse" to the principles of municipal self-administration (Article 28 (2) GG) and connectivity (Article 104a GG) provided for in the Basic Law. Against the backdrop of increasing requirements with regard to climate change, digitalisation and demographic change, etc., the ability of existing small-scale programmes to meet these new challenges is being questioned at all. Since its establishment in 1971, federal and state urban development funding focused until the 1990s almost exclusively on municipal rehabilitation and development measures. Subsequently, the programme structure diverged to reflect the many new requirements. For example, the administrative agreement on urban development funding provided for the following individual programmes until the end of 2019 (VV Städtebauförderung 2019).

In the Federal Republic of Germany, urban development policy derives from the expertise of several branches of government, and as a result extends across various legal sources. These include the Federal Building Code (BauGB) - and in particular Chapter 2 "Special Urban Development Law", which was last amended in 2017. Pursuant to Article 74 (1) of the Basic Law, the legislative competence for the Building Code lies with the federal government, which is responsible for "urban development land transactions, land law (excluding the law on development contributions), and housing subsidy law, old debt assistance law, housing subsidy law, miners' housing law and miners' settlement law". Other legal sources of relevance to urban development policy include the Regional Planning Act (ROG), which also falls within the scope of existing federal legislation, the Act on Protection against Harmful Effects on the Environment Caused by Air Pollution, Noise, Vibrations and Similar Processes (Federal Immissions Control Act (BImSchG)), and the Ordinance on the Use of Land for Building Purposes (Baunutzungsverordnung (BauNVO)). At the level of the Länder, of particular relevance are, among others, the Land planning laws, the Land spatial planning and development programmes, as well as the building regulations of the 16 Länder, which are based on the model building regulations of the Ministries of Construction Working Group (ARGEBAU). The federal government supports urban development measures of the Länder and municipalities with various funding programmes. Of significance here is the administrative agreement on urban development funding to be concluded annually between the federal government and the Länder.

The extent to which urban development policy in the Federal Republic of Germany is now considered part of a comprehensive sustainability policy and thus intended to contribute to the implementation of the New Urban Agenda and the 2030 Agenda becomes clear from the fact that the majority of the relevant legal provisions also contain - explicitly or implicitly - environmental and sustainability-relevant requirements. For example, the new Paragraph 1a of the 2013 amended BauGB ("Supplementary provisions on environmental protection") obliges - in the spirit of the New Urban Agenda (Paragraphs 51 and 69) - the economical use of land and, with reference to the Federal Nature Conservation Act, any compensatory measures for preserving the performance and functionality of ecological balance. Since 2017, the preamble to the Administrative Agreement on Urban Development Funding has also included aspects that are particularly relevant for the sustainable transformation of cities (cf. here in particular preamble points II.2 to 4). Aspects to be given special consideration are as follows: 2). “the requirements of climate protection and adaptation to climate change, including energy renewal in neighbourhoods; 3). the importance of green and open spaces in cities and municipalities for environmental, climate and resource protection, biodiversity, health and social cohesion in urban neighbourhoods; 4). the requirements for adapting infrastructures in a needs-based way [...]".

Municipalities have a range of planning tools at their disposal for their urban development policy, most of which are designed for medium to long-term planning goals. These include – in addition to land use, project and development plans as well as zoning plans – e.g. integrated urban development concepts (ISEK or INSEK), urban development plans or programmes and county development plans as well as individual sectoral plans, such as transport development and noise reduction plans as well as economic, housing and cultural development plans. In addition, many municipalities now have their own climate protection programmes and local sustainability strategies. Coordination of these different sub-plans and strategies can be challenging for the various specialised administrations of the municipalities. Nevertheless, a large number of municipalities are endeavouring to strategically organise urban development as an integrated process. At the same time, the effects of so-called "glocal" trends, such as climate change, demographic change and digitalisation, which are becoming increasingly noticeable at the municipal level, are creating new needs for the transformation of urban infrastructures. As part of this constant change, urban policies and governance approaches must also be constantly realigned and adapted. The methods of urban development are diverse in this respect. In addition to continuous monitoring and benchmarking of individual aspects of urban and neighbourhood development on the basis of (statistical) control indicators, population forecasts, demand and trend analyses of public services, scenario techniques, policy analyses, but also planning forums and quantitative and qualitative methods of citizen participation are important approaches.

In addition to managing vertical and horizontal interfaces in the federal multi-level system, municipalities are increasingly cooperating and "co-producing" with non-state actors from business and civil society to deliver their public services - in some places this occurs somewhat hesitantly and informally. This may be particularly true where it has not yet been possible to achieve the potential benefits and opportunities of a collaborative approach to sustainable urban development and therefore the challenges associated with a strongly participatory or co-productive approach, such as slowing down administrative and planning processes, are superficial. Conflict resolution and interest reconciliation between the public and private sectors have a long tradition in the city. With an increasing sensitivity to urban concerns among members of the public, citizens' participation rights have been successively expanded and formalised. In addition, the change in the understanding of administration in the course of the establishment of the "New Control Model" as a German expression of the New Public Management approach since the early 1990s, also initiated a "participatory turn." In addition to participation in urban land use planning processes for (large-scale) infrastructure projects, citizens can increasingly participate in the preparation of integrated urban development concepts (ISEK), urban model processes or participatory budgets. All in all, governance processes at the local and regional level are now characterised by complex coordination requirements in terms of content as well as institutional and procedural aspects, since conflicts of goals and interests that span different disciplines and periods must increasingly be reconciled.

Urban development policy is a multi-sectional policy field that aims at the further development of the urban area as a whole and/or its neighbourhoods individually, through coordination of various individual policies. In doing so, the spatial, structural and social conditions of individual cities and municipalities must be taken into account, both in their historical genesis and in their regional characteristics. In addition to economic, labour market and social policy issues with local or regional relevance, a variety of aspects, such as housing, land, transport and environmental policy as well as monument preservation concerns of the cities and municipalities must be coordinated and unified. The National Urban Development Policy has existed as a joint task in Germany since 2007.

Urban development therefore always aims at balancing diverse concerns and interests within the framework of city-wide or neighbourhood-related planning processes as well as the promotion and implementation of development measures. The framework for these processes and measures is usually a politically approved urban development concept, which is often developed or updated with public participation. Regulatory requirements, such as the Federal Building Code or the Land Building Codes, serve more as a legal framework that, at least with regard to questions of urban development funding and urban development, marks the limits for relevant processes, and serves less as an instrument for enforcing certain interests - even if both legal sources contain such standards, especially for building construction and civil engineering. The state thus intervenes in private decisions through urban planning processes only to the extent necessary to channel urban growth.

In urban development processes, compromises have to be made across economic, social and ecological interests as well as notions of sustainability. This is exemplified by the issue of land use and consumption, which is becoming increasingly destructive in the course of rapid urbanization. It makes sense therefore for such issues to be addressed by the New Urban Agenda (Paragraphs 51 and 69). In addition to job creation through new businesses in designated commercial areas and the construction of housing, providing sufficient local recreation areas for the growing number of people in the municipalities is equally important, especially since these typically contribute as "green corridors" to the urban microclimate and thus to climate adaptation. Many cities are in fact developing official green space concepts, by anchoring them in urban land use planning or green statutes. They continue to suffer however, from the challenge of political commitment to these regulations, as it is not uncommon for economic interests to lead to individual trade-offs in which ecological and social public welfare concerns take second place to those private interests in favour of costly infrastructure projects.

Urban development policy tends to often rely on a comparatively established and stable network of stakeholders and experts, with professional discourse, competitions and information campaigns typically shaped by urban and spatial planners and architects; and political debates shaped by local and regional politicians and various academic disciplines. The subjects of these debates extend from the international and national to the local model for urban development, which often define tangible social, economic and ecological goals developed in cooperative and participatory processes with broad participation of the various urban stakeholder groups. An example of this is in the Integrated Urban Development Concepts (INSEK), which are a fundamental prerequisite for funding under the federal urban development programmes, making urban development policy more locally and less internationally oriented, in contrast for example to environmental policy - even though the New Urban Agenda, the SDGs, the Urban Agenda for the EU and the New Leipzig Charter were designed as urban development governance approaches at the international or European level. The New Urban Agenda, the 2030 Agenda with its SDGs, the Urban Agenda for the EU (including the "Pact of Amsterdam", the "Working Programme of the Urban Agenda for the EU", the "Riga Declaration" and the "Toledo Declaration") as well as the Leipzig Charter, the EU's URBACT programme and, most recently, the "European Green Deal" are all programmes designed at the international or EU level. Within the framework of its EU Council Presidency in the second half of 2020, the Federal Republic of Germany promoted a new version of the "Leipzig Charter on Sustainable European Cities", which was adopted in 2007 under Germany's last Council Presidency. The "New Leipzig Charter - the transformative power of cities for the common good" was newly adopted in December 2020 and is a more robust approach to strengthening the "green, just and productive city" in Europe. To this end, the charter identifies five approaches to "good urban governance" which include the common good orientation, the integrated approach, participation and co-creation, multi-level cooperation and the place-based approach.

The Federal Ministry of the Interior, for Building and Home Affairs (BMI) has meanwhile promoted the establishment of various "International City Learning Networks" aimed at strategic urban development through dialogue. These include the "Dialogues for Urban Change (D4UC)" involving cities in Germany and the USA, South Africa and Ukraine, or the "International Smart Cities Network" (ISCN). In the majority of these networks and programmes, regeneration of disadvantaged neighbourhoods through civic and urban stakeholder participation are key points of overlap. Activities also include research alliances across public authorities, as for example the Federal Institute for Research on Building, Urban Affairs and Spatial Development (BBSR) with the National Institute of Urban Affairs (NIUA), which analyses SDG 11.3.1 data, prepares visual mapping, and formulates evidence-based recommendations for action.

In the New Urban Agenda, the promotion of "sustainable transport infrastructures and services" or more generally "sustainable urban mobility systems" plays an important role. Although not more precisely defined in certain key paragraphs, (e.g. 34, 54, or 118), it does generally become clear that the goals are to reduce congestion and environmental pollution (Paragraph 54), to ensure safety (Paragraph 113), and to enable mobility for all people (Paragraphs 34, 54, 70, 113, 114). From these overarching goals, a focus can be derived on strengthening public transport, which is also explicitly addressed in Paragraph 114a. On the other hand, increasing efficiency and reducing emissions in motorised individual transport, for example by expanding the infrastructure for e-mobility and through "smart" ways of traffic control, is less important. Only Paragraph 118 refers to the need to develop financing instruments to improve transport and mobility systems and infrastructure with technology-based innovations. Paragraphs 113, 118 and 114a deal with the targeted promotion of active and thus also health-promoting mobility in walking and cycling, whereby the latter also explicitly demands priority over motorised private transport. Finally, Paragraphs 114c-d refers to the reduction of travel and transport needs through improved access to goods and services close to home.

The majority of German cities today suffer from significant traffic congestion. This is evidenced, for example, by the TomTom Traffic Index, which in 2019 found an average daily travel time increase of 17 to 34% due to congestion or traffic obstructions for each of the 26 major German cities analysed - with an upward trend for the majority of all cities studied. However, congestion does not only affect private motorised transport and the density of road infrastructure use, but also the significant infrastructure bottlenecks in public transport, which reduce the quality of service. In addition, the settlement structure of many cities and in particular of their surrounding areas is insufficiently public transport friendly). Various obstacles often prohibit a reorientation of the "modal split" in the sense of sustainable urban and regional development. These include the high utilisation of existing capacities, the high investment requirements with sometimes very long planning and realisation phases, the narrow financial scope of action of the municipal public transport authorities, especially with regard to the financing of an attractive offer, the lack of personnel in the municipalities and the transport companies, but also the rejection of new public transport projects by the citizens. Furthermore, it is difficult for the municipalities to actually spend the significantly increased investment funds for new projects within the framework of the clean air and climate protection policy. From the user's perspective, hikes in fares at the city limits can lead to a perception that travelling by public transport is more expensive than using one's own car. The coronavirus pandemic, with its dominant trend towards working from home, has sharpened the focus on the lack of fare options for part-time employees and employees with varying work locations. Implementation of innovative passenger transport services, such as on-demand transport, has been hindered by the Passenger Transport Act (PBefG), which, however, is to be removed by an amendment during the current legislative period.

The New Urban Agenda provides in Paragraph 114 for the promotion of access for all people to "safe, age- and gender-responsive, affordable, accessible and sustainable urban mobility [...] systems". This demand can – to some extent – be captured by the indicator of the so-called "modal split", i.a. from the set of SDG indicators for municipalities. The modal split describes "the distribution of transport volume and transport performance among the different transport modalities (usually walking, cycling, public transport and motorised private transport). In this way, the indicator provides a picture of mobility behaviour within the municipality. In the long term, the shares of non-motorised transport (i.e. walking and cycling) and public transport should be increased in order to ensure the sustainability of transport systems". The informative value of this indicator is limited if the modal split only refers to the mode of transport used by the local resident population, because increasing commuter traffic into the city, for example, is not taken into account. Moreover, the relative modal split cannot reflect a possible absolute growth in traffic and thus the traffic load due to more frequent trips, for example. Overall, the municipalities studied here have a significantly above-average share of environmentally friendly modes of transport compared to the overall German value - with the lowest shares of motorised private transport (MIV) in Cologne and Darmstadt. While journeys on foot are relatively evenly distributed across all the cities studied and between the spatial types (18 to 29%), the shares of cycling differ greatly in some cases between the cities, even within the same spatial type (8 to 27%). This independence of settlement structure conditions indicates that the attractiveness of cycling depends on various factors that can be actively shaped by the municipality. With increasing rural character, public passenger transport typically decreases, while private motorised transport increases.

The shares of the modes of transport have remained relatively stable over several years. The private car dominates the choice of means of transport in the cities and much more so in Germany as a whole, thus leading all other modes of transport - with a slight downward trend. Within the environmental alliance, the share of walking is also declining slightly. These shares are balanced out by marginal growth in public transport and cycling. Cycling in particular has experienced an upswing, especially since the outbreak of the Corona pandemic. This can be observed not least in the establishment of many so-called pop-up cycle paths in the city centres. Together with the decreasing share in public transport, the modal split in 2020 has thus revealed a previously unknown dynamic.

In Paragraph 114 of the New Urban Agenda, the modal split is discussed but also the goal of reducing motorised individual transport, which can be approximated by the density of passenger cars. This indicator is defined as follows: "The number of registered passenger cars has been rising continuously for years. This exacerbates considerably the distribution problem of public space both in rural and urban areas and counteracts efforts to make transport systems more sustainable and, above all, more accessible. The tendency of political parties and administrations to expand infrastructure in response to traffic densities has often led to an even higher utilisation of infrastructure". High traffic density also has negative consequences for healthy living conditions and environmental justice issues in the city and demands considerable economic and ecological costs. It shows that despite intensified efforts towards environmentally compatible and sustainable urban mobility in recent years. Traffic density has increased slightly everywhere since 2010. As expected, it is higher in the smaller municipalities than in the large cities and higher than the average for Germany as a whole. In Eltville/Rhein, as a medium-sized centre, it is even at a significantly higher level than in the far more rural partner municipalities of Niebüll and Baruth / Mark. Eltville does not have a city-owned public transport system. Rather, the town is served by a regional transport company that in recent years has focused on expanding its services elsewhere. According to the partners involved, the public transport system is inadequate, especially in the peripheral areas of the city. As many residents commute to the larger cities in the Rhine-Main region, the traffic density in the city is above average.

In several places, the New Urban Agenda specifically addresses the expansion of and access to public transport as well as appropriate funding to ensure sustainable urban mobility (see Paragraphs 36, 114a, 114b, 118). German metropolises with more than 1 million inhabitants Berlin, Hamburg, Munich and Cologne alone carry more than a quarter of the 9 billion passengers who use public transport in Germany each year. Together with other of the 12 largest cities in Germany, almost half of all public transport passengers are carried by buses and urban railways (underground, light rail, tram). These figures underscore the importance of public transport in urban areas, but also shows, against the background of the population distribution, that the importance of public transport for the absolute majority of citizens (approx. 80%) living in medium-sized cities, small towns and rural areas is relatively low.

If the demand for public transport is compared with the supply of the municipalities, growing differences can be observed with increasing city size. Especially in the megacities, but also in the whole of Germany, adequately meeting the increasing demand in recent years has been impossible, so that the burden on infrastructure has increased considerably in some cases.

The rail network density in the five participating cities additionally supports the need for improvements in public transport - here especially in rail transit. For the observation period from 2010, it is clear that this indicator has largely stagnated and, in the case of Mannheim, even declined, which could be due to the decommissioning or dismantling of freight transport infrastructures.

All motorised means of transport - especially those powered by fossil fuels - emit environmental oxides that are both problematic for urban ecosystems and can affect the health of the population, resulting in considerable economic follow-up costs. The issue of health risks applies to traffic noise and air pollutants, especially particulate matter and nitrogen oxides and are usually greater for socially disadvantaged groups who predominantly reside in the more favourable locations, which are, however, more exposed to noise and pollutants. Therefore, this is also particularly problematic from a social perspective. The New Urban Agenda highlights the financial, environmental and public health costs of inefficient mobility, in Paragraph 54.

Figure 26 shows an estimate of the annual averaged and area modelled exposure to nitrogen dioxide at stationary ambient air monitoring stations in all partner municipalities. Overall, the load is decreasing, although this decrease is not constant.

The goal of improving road safety "[…] with special attention to the needs of all women and girls, as well as children and youth, older persons and persons with disabilities and those in vulnerable situations […]" is provided in Paragraph 113 of the New Urban Agenda. This emphasises the safety of pedestrians - especially schoolchildren - and cyclists, as well as motorbike safety - although the latter is likely to be a priority, especially in countries of the global south. The indicator catalogue from the project "SDG Indicators for Municipalities" contains the indicator "Number of traffic accidents". This is a measure for assessing general road safety. "Worldwide, road traffic accidents are the most common cause of death among adolescents and young adults, regardless of a country's economic situation. There is "an imbalance in mortality and probability with regard to the mode of transport". This means that road users "who pose the least risk of an accident are disproportionately often injured or killed". Pedestrians and cyclists are therefore "more likely to be injured and killed by cars".

In recent years, the range of mobility options called for by the New Urban Agenda has grown steadily. In this way, access to sustainable transport systems has been strengthened (Paragraph 114). In particular, new and mostly digital-based mobility offers and services can enable sustainable movement within and between communities. A comprehensive variety of choices from car sharing to ride sharing and car-pooling to multimodal journey planning services mostly only exist in urban areas, as the fixed costs are too high to allow operators to perform economically, especially in the case of classic sharing options (B2C) in less populated regions.

With a growth of over 25% compared to the previous year, there were around 25,400 Car-Sharing vehicles in Germany in 2020. Car-Sharing services were able to benefit from digitalisation of access, making reservation and booking easier and more customer-friendly. While the market is experiencing saturation in large cities with high population numbers, Car-Sharing is spreading more and more in medium-sized cities such as Darmstadt. More than 95% of large cities with more than 100,000 inhabitants are served by station-based or free-floating Car-Sharing services. Although this proportion of municipalities with Car-Sharing services decreases as the number of inhabitants decreases - only 4.3% of municipalities with less than 20,000 inhabitants have Car-Sharing services - in medium-sized municipalities with up to 50,000 inhabitants, the proportion is still 46.8%. More than 2 million citizens are registered as Car-Sharing customers in Germany. Overall, however, measured in terms of traffic volume, Car-Sharing services still represent a niche option.

According to the New Urban Agenda, the use of sustainable transport systems should also be promoted through the improved provision of complementary services (Paragraph 66). For example, access to modern information and communication technologies enables interaction and connectivity between urban and rural areas for all people. Public transport apps and mobile ticket purchasing make the use of sustainable mobility options and services much easier. A population survey on public transport app use in 2017 shows that many people already use public transport apps. In Stuttgart, this is the case for as many as 80% of respondents. However, mobile ticket purchase is less frequently adopted (see Figure 30). Accessibility for the entire population through a mobile network plays an essential role here and should also be strengthened with regard to the New Urban Agenda (Paragraph 50). Despite the high growth rates of new mobility services in recent years, the absolute usage figures currently remain too low and concentrated in larger urban areas for a significant contribution to be made to transport transition for municipalities and citizens.

The report presented an opportunity to focus indepth on questions of multi-level and indicator-based reporting with the direct involvement of municipalities. In order to cope with this challenging task, while remaining within the limited scope of this report, some basic but necessary selection decisions were made: of sustainability topics and fields of action, of a reference framework in the form of an appropriate indicator system, and of partner municipalities to participate in the monitoring process.

The New Urban Agenda addresses various fields of action for (municipal) sustainability activities. Since these cannot be discussed here in their entirety, the topics of climate change and climate adaptation, as well as mobility in the urban-rural context, were selected to document the implementation progress. Either a one-day or one-and-a-half-day (virtual) workshop or several telephone interviews were conducted with each of the municipalities to discuss indicator-based sustainability management for the implementation of the goals of the NUA. Municipalities were advised how to further expand the respective SDGs in their own municipality through appropriate data collection, data preparation and data processing. The pre-selection of indicators formed the basis of workshop discussions and interviews with the partner municipalities, at which time the city-specific relevance of pre-selected indicators was explored, as was data availability and possible conflicts of objectives.

In order to intensify progress in the implementation of the New Urban Agenda and the 2030 Agenda, it is therefore necessary to revise the level of detail practiced in current municipal monitoring systems. Only when a large number of municipalities provide a systematic account of their own sustainability activities can the aggregate contribution of the municipal level to the achievement of the New Urban Agenda and the SDGs as a whole be assessed. However, we must not lose sight of the actual purpose of such monitoring. A systematic and indicator-based recording of municipal sustainability activities contributes significantly to raising political and social awareness. Ultimately, this is also the motivation for all the municipalities with which we have worked, in the context of this report. Raising the awareness of their own administration and population is of central importance – specifically regarding a " global commitment to sustainable urban development as a critical step for realizing sustainable development in an integrated and coordinated manner at the global, regional, national, subnational and local levels, with the participation of all relevant actors" (Paragraph 9 New Urban Agenda).

The technical and practical challenges municipalities experience in establishing sustainability monitoring, and accelerating expansion of sustainability activities, include a lack of human resources, a situation which is less acute in the larger cities. Municipalities with fewer than 5,000 inhabitants and an administration with, for example, 25 employees, each of whom has to work on various topics, typically have a minimal time budget for elaborate sustainability monitoring. Moreover, such municipalities naturally do not have their own statistics departments.

But even in “forerunner” municipalities, the data issue remains the stumbling point. Current data from official statistics are only available for some of the sustainability indicators for all local authorities in Germany. Thus, the municipalities have to collect their own data for many indicators, which is always a question of resources.